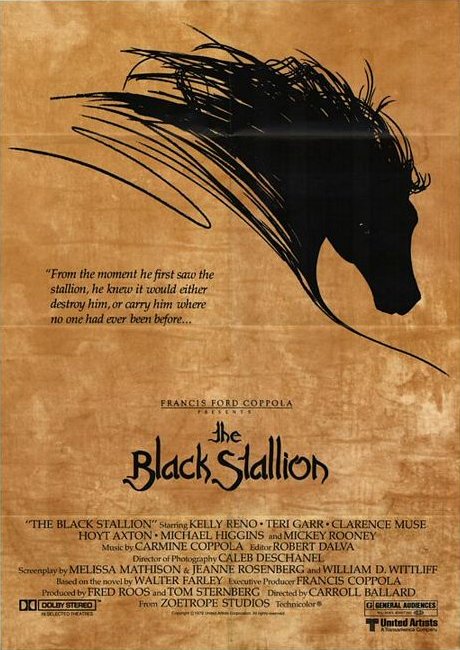

Celebrating the 39th anniversary of the production start of “The Black Stallion”.

This is a fairly accurate description of the days, and weeks, and years that went into the making of the film. There are a few liberties he has taken and some things omitted to keep the story flowing, but all and all it takes me back to my younger days!

Thanks TMC and Roger Fristoe for this nice article on the making of the movie!

If you want a piece of the past for your very own take a Bucephalus home!

Behind the Camera On THE BLACK STALLION

Filming of The Black Stallion began in Toronto on July 4, 1977. The summer of 1977 in Canada was one of the wettest and hottest on record, and delays were caused by the torrents of rain that flooded the Woodbine Racetrack, creating a two-foot-deep layer of mud. At the end of August the film crew headed for the sunny Mediterranean, where they faced a new set of problems.

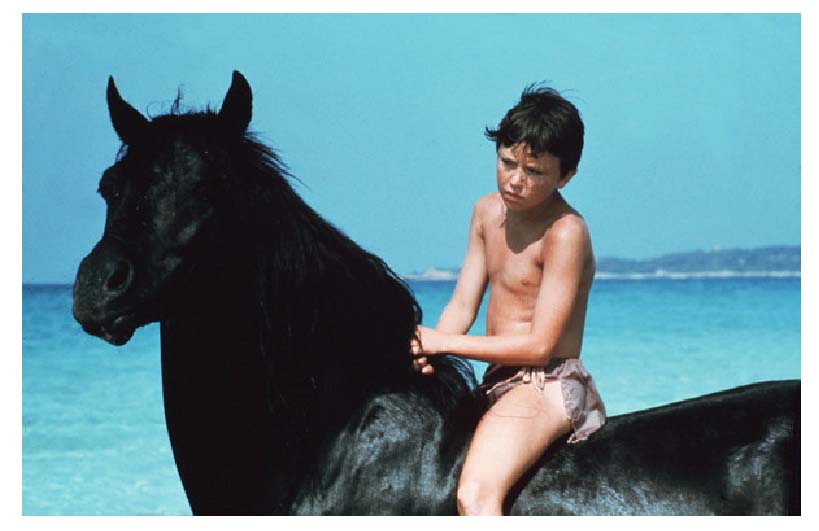

The first location in Sardinia was near the town of Marina di Arbus, where the horses were transported by a van containing portable stalls that were set up near the filming site, and the crew had to hand-carry the cameras and other equipment over the sand dunes. That situation was repeated at various other locations all over Sardinia, with exposure to sun, sand, sea and dysentery causing considerable discomfort for the crew. Other locations there included Capo Caccia, Capo Camino, Costa Paradiso, Cala Ganone and San Teodoro, which sported a mile-long stretch of fine white sand that was perfect for the boy’s first ride on the stallion. Temperatures in Sardinia could become quite cold, and Reno shivered through scenes where he wore little clothing and was often in the water.

A sequence that made everyone especially apprehensive in its filming was the one where the Black stomps and kills a cobra that is threatening Alec. A group of snakes was flown in from Milan with a handler, Carlo Guidi, who assured the filmmakers that his cobras had been milked of their deadly venom. Just in case, a special serum was kept on hand but, thankfully, did not have to be administered.

The last major segment to be filmed was the sinking of the ship at Rome’s Cinecitta Studios, which features a huge outdoor water tank. Two portions of the ship, an actual-size deck and stern, were designed by art director Aurelio Crugnola and assembled in the tank, a process that took three months. These were the largest sets ever built in the tank. The stern was set on a platform in the tank, with cables attached to pull it into the water as it sinks. Filming of the shipwreck sequence lasted three weeks.

The movie, at a cost of $4.5 million, took two years to complete, with shooting also done at various locations in the U.S. Kelly Reno, whose only trips outside Colorado had been to North Dakota and California, was chaperoned by his parents while visiting the widespread locations. Despite their presence, he became homesick and later noted that, “In Rome, I’d have paid $10,000 for a McDonald’s hamburger. You never know how much you want that if after a week all you get is spaghetti. And I had me a little wine, but after a week, I started drinking cokes again.”

Early in the shooting, the untrained Reno spoiled some takes by looking at the camera. He recalled Ballard telling him, “‘This is the way it is…do it.’ If I didn’t get it done, we’d just have to do it all over again. Lines weren’t a problem. I had a lot of them, but they weren’t in whole, long scenes. And I could put it in other words if the meaning was the same – that was all right with Carroll.” Reno did most of his own stunts, riding bareback and with a racing saddle, falling from a galloping horse and swimming with it. A stunt double stepped in only for racing scenes, when his character was to ride a thoroughbred running at top speed: “I was too small to hold him back.”

Reno recalled that his most difficult scene was the shipwreck, which happens during a raging storm and was shot at night. “They had wind and rain and fire and smoke,” he said. “I spent a lot of time in the tank, not being able to touch bottom, while they made these waves that came very far over my head.” As the boy and horse thrashed in the foreground, the realistic model ship was burnt and sunk headfirst in the tank. For such scenes, great demands were made of the horse playing the Black. The owners of Cass Ole had stipulated that he was not to be used in swimming, fighting or racing sequences, so other horses doubled for him in these and other challenging situations.

The main double was Fae Jur, the spirited horse from California that Ballard had once considered for the role of the Black. He is the horse in the memorable scene where Alec tempts the stallion with seaweed on the beach. Fae Jur’s naturally independent nature made his approaches and retreats very believable. He loved fake-fighting and also was used in the sequences where the Black stamps on a cobra and where the high-strung stallion strikes out at another horse just before the big race.

Junior and Star, two stunt horses owned by the Randall family, stepped in for Cass Ole when scenes required strenuous fighting, running, jumping and swimming. Star enacted the scene where the Black gets tangled in rope and caught between two rocks. He was so unconcerned about being tied up and forced to sit that Corky Randall had to toss pebbles at him to get him to simulate any kind of agitation.

None of the equine doubles liked being in the water, so horses were brought in from the lagoons of Camargue in France for the underwater shots of the Black swimming in the sea. Cinematographer Caleb Deschanel recalled in an interview that the swimming horses “had pot bellies and incredibly ugly faces.” But when they “came into the water and started swimming, they looked unbelievably graceful. They were the ugliest animals you’ve ever seen, but underwater…they were like Nijinsky.” The crew nicknamed these horses Pete and Repete because of the numerous takes required to get the appropriate underwater footage.

There is a scene in the water where the Black is swimming towards Alec and suddenly tips over in the waves, with his head underwater and his hooves pawing in the air. This was actually an accident captured on film, as too much force was applied to the guide bars attached to control the stunt horse’s movements. There was much alarm on the set as he sank below the surface, and great relief when he managed to right himself again and raise his head above the water. The crew of The Black Stallion was especially proud of the fact that, despite all the difficult stunts throughout filming, no horse was injured in any way.

Despite all the doubling, Cass Ole remained the star of the film and appears in about 80 per cent of the horse footage. He learned to express anger by putting his ears back, rearing on his hind legs and stomping the ground – and could also turn soft and loving on cue, nodding his head and giving pretend kisses to Reno. Even his facial expressions changed. “It was amazing,” said Corky Randall. “I never met a horse before who wanted to be an actor.” Only once did the stallion lose patience – during the bareback ride on the beach when Alec holds up his hands in triumph. Cass Ole suddenly bolted, giving Reno a much wilder ride than he expected. The crew was terrified for the boy, but he was a capable rider who lowered his hands to grab the horse’s mane and hang on for dear life.

Cass Ole was naturally black, although he had white markings on his pasterns and a white star on his forehead that had to be dyed before filming. During some scenes in the water the dye fades and one can glimpse suggestions of the white markings. Some of the horse doubles – including the swimming horses, which were white – had their entire bodies dyed black. Like many American horses Cass Ole had his mane trimmed into a “bridle path” that allows a bridle or halter to lie flat against the neck and head. Although he had the long mane typical of his breed, extensions were stitched into the hair of Cass Ole’s mane to hide the bridle path and create the luxurious, flowing mane that is seen on the screen.

Ballard credited Deschanel for many of the movie’s signature touches, especially during the first half of the film, when dialogue is minimal and the images are everything. “Caleb has a tremendous eye, and he can invent things right on the spot,” Ballard said. “Really, some of the neatest shots in the movie are things I didn’t even know he was shooting.” Neither director nor cinematographer had ever done any underwater work, and Deschanel improvised his equipment for those scenes. Ballard came to depend upon his associate to see him through tough times during filming. He recalled a particularly trying day when he was convinced the project “was a catastrophe. Caleb and I were walking together, trying to get back to the car, and we came across this river that just seemed to appear out of nowhere. We had to get across the river to get where we were going and Caleb said, ‘Come on, get on my back and I’ll carry you across.’ I’ll never forget it. He was kind of like that through the whole film.”

Concert composer William Russo was initially given the assignment of scoring The Black Stallion, but when he and Ballard couldn’t agree on what the music should be like, producer Francis Ford Coppola stepped in and hired his father, Carmine Coppola, who had scored his son’s Godfather movies. Carmine created an unobtrusive yet evocative score that was supplemented with music by Shirley Walker.

Author Farley had reservations about his signature story being filmed and feared that the novel might not translate successfully to a new medium. Happily, the movie exceeded his expectations in remaining true to the original and finding its own artistic identity. “They did a beautiful job,” he conceded. (A sequel, The Black Stallion Returns, filmed in Italy in 1983, failed to live up to the author’s standards. A new musical score by Georges Delerue is considered by some to be that film’s most impressive element.)

Once completed, The Black Stallion was shelved for two years by United Artists. Ballard recalled the studio “suits” complaining, “What is this, some kind of an art film for kids?” It took the full clout of Francis Ford Coppola to see that the film finally reached theaters. Many critics were ecstatic; Roger Ebert named the film the best of the year, and Pauline Kael described it as “proof that even children who have grown up with television and may never have been exposed to a good movie can respond to the real thing when they see it.” The movie quickly became a box-office hit and won two Oscar® nominations including one for Mickey Rooney, whose career resurgence at the time also included a Broadway triumph in Sugar Babies. New York magazine described him as “a figure out of a semi-mystical past,” and Rooney himself declared that “My cup runneth over.”

Among the innovations of sound editor Alan Splet, who won a special Oscar® for his work, was attaching microphones to the underside of the horse during the racing scenes to catch his actual hoof-beats and breathing. There was outrage in some quarters when Caleb Deschanel’s ravishing cinematography failed to even be nominated for an Academy Award. Deschanel, then 34, commented, “I’m disappointed. The fact that so many people told me I was sure to get the nomination has made it harder to take. On the other hand, who am I? I’m just a young punk making his name in this business…”

By Roger Fristoe

Want to read more? Click here.

Thanks for reading …. and writing!!